Good & Evil: More Dimensions than a Bag of Holding

Ye olde TL;DR - By aligning good and evil to party goals, players experience a more morally textured game.

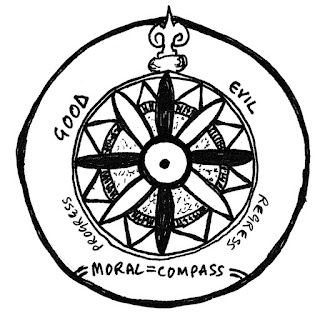

By now, Dungeons and Dragons’ modern 9-point alignment system is so familiar as to be cliche, as countless memes readily prove. But although this framework dates back to AD&D 1st Edition, it was not D&D’s initial alignment system. Rather, Original Dungeons and Dragons’ (1974) system was, superficially, much simpler, consisting of Law, Neutrality, and Chaos.

Good and Evil were not explicitly delineated, but they were by no means neglected. Crucial mechanics hinged on, and in turn reinforced, this polarity. By being coyly terse on Good and Evil, the game leaves more of their interplay to explore through gameplay. Essentially, it posits that there is Good and Evil, and lets the players figure out the rest.

This makes the duality of Good and Evil as freeform as adventuring itself. Like with experience points, there are some guidelines for what constitutes progress, but what acceptable means are is open to debate.

No guiding stars, only torchlight

Consider this: align “Good” with actions which lead to constructive impact on party goals and advancement, and “Evil” with actions which lead to destructive impact on the same. What happens? What truly is Good for the party?

For one thing, Good and Evil become more about actions than characters. The spectrum measures outcomes, so your action is Good or Evil. With every subsequent action, characters resonate with Good or Evil as the preponderance of their actions’ consequences do.

In turn, a moral alignment guided by consequences shifts focus away from intentions. It’s easy to want a Good outcome, but much more challenging to produce a Good outcome. The spirit of the game is precisely the manipulation of the world, from the character’s circumstance, to make happen what you will. Does anyone really only act per their alignment?

Sinners and saints cast stones

Crucially, this structure encourages more systemic thinking. The sands are ever-shifting, yes, but firm footing lies in considering the ripples that actions emanate.

What is Good in the short-term may be Evil in the long-term (or vice versa). Robbing a town may well get you gold, and thereby experience, but that turns the town against you, and the region follows. Note, though, that gold, not valuables, earn experience points. So when the party’s outlawry denies them the commercial opportunities to liquidate valuables, their action will have forestalled advancement in the end.

Similarly, what is Good today may be Evil tomorrow (or vice versa). Imagine the characters pledge fealty to a ruling noble, who then orders an incursion on the neighboring lands. Prior to their oath, attacking the territory would have been Evil, but depending on the severity of the penalties for refusing their liege-lord, not attacking could be Evil.

These are but a taste of the thought patterns that this moral framework can beget. However, they all induce a mindset which treats the game world as a system, not a mere backdrop. Ultimately, it’s the world’s reaction to player action that judges their “alignment” to Good or Evil. Its verdicts may surprise you, but they provide the moral texture that broaden options and deepen immersion.

Comments

Post a Comment